It's A Magic Carpet Ride

On Jutta Hipp, Leonard Feather, Power, Jazz & Unruly Ideas

I was excited to be asked to participate in Mark Mordue’s brand new Addi Rd Writer’s Festival that took place last week, with the prevailing theme of ‘An Unruly Idea’. I was on a panel called ‘Songbirds and Broken Wings’, the title of which made me think about Jutta Hipp. Her story haunted me. She was a German jazz pianist, the first female musician signed to the prestigious Blue Note Records in 1954, releasing only a few albums with them before disappearing, never to be heard of again.

So at the writer’s festival I talked a little about my fascination with hidden histories and sung the song that I was inspired to write about her with Sam Worrad, who composed the music. We recorded it for our album ‘Everyone You Ever Knew (Is Coming Back To Haunt You)’ in 2015, along with Ken Gormley and Cec Condon. A bit like Jutta herself, the song was a bit of a one off, a moment in time - it was rehearsed a few times, recorded with love, then never performed again.

Jutta started out playing classical piano as a child but discovered jazz as a young woman during the war - considered’ degenerate music’ - in secret underground radio listening sessions, during a time when anyone who played it or listened to it was subject to Nazi punishment. But Jutta fell in love with it anyway, transcribing jazz tunes in the basement under the cover of bombing raids in her native Leipzig, practising in clandestine meetups with other secret jazz heads. Post war, she was excited to meet the American troops stationed there and talk jazz with them - she was terribly disappointed to discover they were all into country music. She began studying painting at the Academy of Arts but when Soviet troops took control of Leipzig, they wanted her to design propaganda posters. Instead, Jutta made a dangerous escape across the border into West Germany, arriving with nothing but the clothes on her back and some records, finding gigs in circus bands, ‘hot clubs’, military nightclubs, performing gruelling hours - generally from 7pm until 5am, with only one break, often 7 days a week. She told an interviewer ‘I played for anyone that would hire me and sometimes, when our band finished, I stayed on to play with the next one. It was important to me to be accepted not just as ‘a girl’, but as an equal to other musicians doing the things I like.’

She gave birth to a baby boy in 1948, but the father was a Black American GI, legally unable to claim paternity of a child born to a white mother. When he was sent back to the USA, she was forced to give the baby up for adoption. She worked harder. She earned herself the moniker ‘Europe’s First Lady of Jazz’.

Leonard Feather was a renowned and extremely influential American jazz critic, producer, composer and general mover and shaker. While touring West Germany with Billie Holiday, on the advice of some US musicians who had heard her play, he tracked Jutta down playing the late shift in a cellar club and was duly impressed by her hard earned cool jazz chops. Leonard arranged for her to record for Blue Note and invited her to come to New York, promising to look after her and help her book shows, and with nothing much to keep her in Europe, she agreed, setting sail across the ocean with the grand sum of $50 in her purse and no idea of what to expect.

On her arrival in New York in 1955, she stayed with Leonard Feather and his wife and children, he sung her praises and hustled shows for her and she began a six month residency with a trio at the Hickory House, a happening jazz club, and performed at Newport Jazz Festival the following year. Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus and Charlie Parker were fans of her spare, silvery be-bop style. Jutta Hipp was on the rise. But though she passionately loved playing, she suffered from a terrible potpourri of stage fright, bad anxiety, excruciating period pains and an utter lack of hunger for fame. She didn’t want to be a band leader, didn’t want to be a star, didn’t like the pressure, she felt like people stared at her as if she was ‘a strange animal’. She just loved jazz.

Leonard Feather's Jutta Hipp Introduction at Hickory House

'Violets For Your Furs' Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims

She started drinking to self medicate. She turned down a romantic advance from Leonard Feather, then further hurt his ego when she refused to record one of his compositions because she didn’t think it was good enough. She believed that jazz should take you away like it was like a magic carpet ride.

A year or so after her arrival in America, Leonard began bad mouthing her around town, telling club owners she was a drunk, weird and withdrawn and not as talented as he thought. Gigs fell away and though she struggled on for a few years, eking out a living with occasional gigs, eventually she could no longer pay her rent. Homeless and alone in a strange country, Jutta knew something had to give. She was a survivor. In 1960, she simply turned her back on her life as a performer, and hit restart. She moved to Sunnyside, Queens, quit drinking and worked in a clothing alterations factory for the next 35 years.

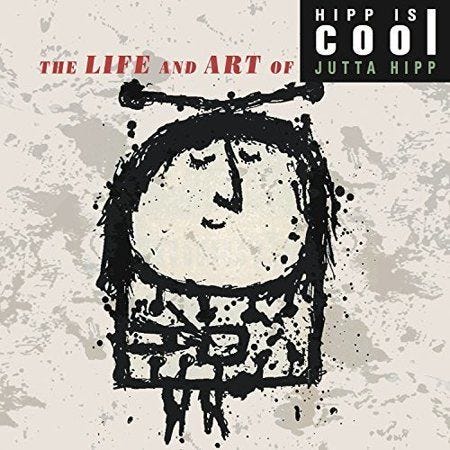

She never played a piano again, although her love for jazz remained unabated and she’d stand in the shadows in clubs to watch her favourite players, alone, often sketching. She was a multi-talented creative artist, skilled at photography, watercolour painting, drawing and poetry. Her cartoon like portraits of jazz musicians were published in German magazines.

A few years before her death in 2003, the general manager of Blue Note Records went through the books and discovered $40,000 in unpaid royalties owed to Jutta. He managed to track her down through the wife of saxophonist Lee Konitz, who still kept in touch with her, and took a chauffeured car down to her little Queens apartment to present her with the check in person over tea and cake. She was astonished. By then she was retired, living alone on Social Security and a small pension. None of her coworkers had any clue of her former life, or even knew she could play piano, until someone found her obituary in the New York Times, which said she had stopped playing in 1958 because of ‘low self confidence’. Her obit in the Independent said she had ‘a lack of respect for her own talent’.

Leonard Feather literally wrote The Encyclopaedia of Jazz, in which he disparaged her talents and said she had ‘become uninteresting’. He removed her entirely from the revised edition some years later. Her career blossomed and withered at the whim of a disgruntled powerful man. Even her historical legacy was dismissed and reduced by him. Her child was taken from her by a racist, authoritarian government . She never reunited with her son, although he knows who his mother was. Though there were very few other female jazz musicians playing in the 1950’s, despite her impressive accomplishments and her four Blue Note albums, she didn’t even rate a mention in Richard Cook’s new definitive Encyclopaedia of Jazz (2006 ), with over 2000 entries of jazz artists.

The part about Jutta’s story that really bothers me is that without the incredible research done by one woman, Katja von Shuttenbach, who admired Jutta Hipp and dug far deeper, we would have believed the accepted version that she simply gave up on herself rather than the true story that has been uncovered via Katja’s years of meticulous research - that despite possessing the requisite talent and resilience to make for a successful creative career - even if she didn’t want to be a star - her reputation was pretty much destroyed by Leonard Feather, and the work disappeared.

Of course, hers is just one woman’s story in a world of many, many stories of women who have not fulfilled their potential due to the power wielded by gatekeepers but there’s something in Jutta Hipp’s story that makes me want to celebrate who she was, and to rail against her being written off. I’m not alone. Signed copies of her early records sell for over a thousand dollars on eBay now. A street is named after her in Germany. There are box set reissues and a book in the works about her life and interviews from her later years are being translated or digitised and entering the public sphere. Interest is still building.

Although my song is far more obscure than even Jutta Hipp is, it still makes me feel good to sing about her because I believe its important to uncover more true stories of what women have endured and achieved despite all the odds stacked against them, so we don’t keep buying the version of history that takes away her story.

Go listen to some Jutta Hipp playing some silvery swinging hard bop cool jazz sometime, close your eyes and just imagine….

Listen to 'Jutta' by Lo Carmen (from 'Everyone You Ever Knew (Is Coming Back To Haunt You)

Further reading:

https://www.jazzwax.com/2013/05/jutta-hipp-the-inside-story.html

https://longreads.com/2017/08/04/the-brief-career-and-self-imposed-exile-of-jutta-hipp-jazz-pianist/