For The Record

On The Importance Of Mistakes, Dreams & Breaking All The Rules

As a music maker, I can’t quite believe that this mesmerising little clip from Holiday Records is my new record being pressed:

Transatlantic Light will be out in the world next Friday, and the culmination of the whole process has got me thinking a lot about records, how they get here and what they mean to us….

As human beings, we can learn so many lessons from music and its creation.

The recording of music is such a mysterious and hallowed process, mired in expensive technology and deals and big money, but much of the most idolised music ever committed to tape broke all the rules.

I’m not advocating for sloppiness or rushed recordings, just for trusting yourself, for being unafraid of thinking something is right, or within your reach, when everything you’ve been told warns you not to trust that instinct. Go where your river leads you.

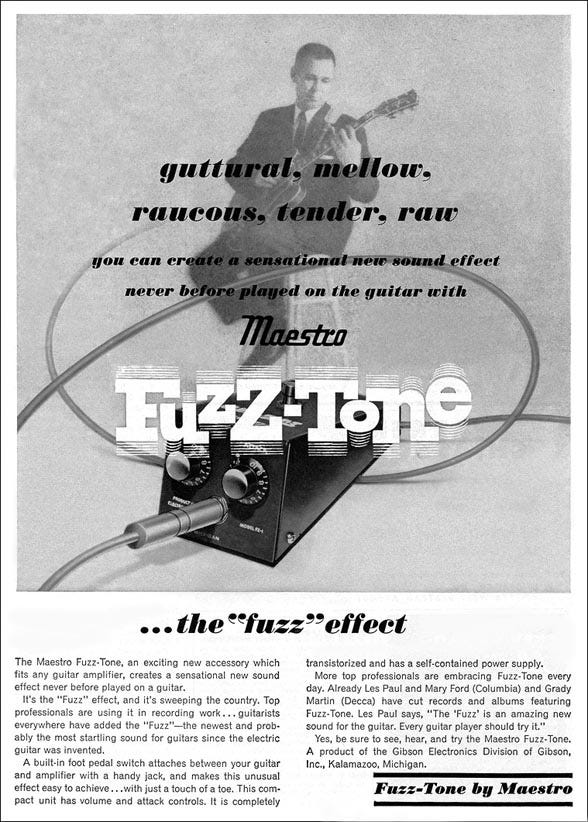

Way back in 1960, the country singer Marty Robbins was putting ‘Don’t Worry’ down to tape at Nashville studio the Quonset Hut with an engineer called Glenn Snoddy. A transformer in the recording console shorted and ‘ruined’ the guitar sound, right as this instrumental began. Snoddy was not happy, but Marty and his producer loved the resulting crazy fuzz sound so much they insisted on leaving it in.

After requests to replicate this tone from artists such as Nancy Sinatra started rolling in to the Quonset, Snoddy set to work reverse-engineering the effect – ‘It’s mellow, it’s tender, it’s raw!’ proclaimed the first demonstration – leading the way for the distortion revolution and paving the way for the Big Muff, one of the most popular purveyors of hot fuzz tone.

The Big Muff was the first pedal created by Electro-Harmonix and immediately hit the right nerve with guitarists. It made something like the sound Dave Davies from The Kinks invented in 1963 when he first slashed the speaker cone of his Elpico amp with a razor blade in frustration and was shocked, surprised and delighted to hear what he has often described as ‘the amazing roar’ that erupted, creating that iconic riff that nails ‘You Really Got Me’ to the wall. The sound rock guitarists dream of making.

Young Carlos Santana sent in a cheque, with a discount coupon clipped from Guitar Player magazine, for his first Big Muff in 1971. Owner Mike Matthews still has it. Mike is the Willy Wonka of sound effect pedals, his factory seemingly staffed entirely by women who meticulously hand-test each item. One woman’s sole job is to plug each newly minted pedal into a machine called the Oscilloscope to check the voltage of the electrical signal in the resulting wave forms.

Brian Eno once noted, ‘The temptation of the technology is to smooth everything out.’ But there’s so much more to be said for raw, unvarnished appeal. The Go-Go’s Kathy Valentine revealed in her great book that their mammoth hit ‘Vacation’ was mastered directly from an early cassette studio mix-down given to the band to listen to, after they all agreed the final pro-mix just didn’t recreate that certain something the dashed- off tape possessed.

The much-copied guitar riff on Guns N’ Roses’ number one hit ‘Sweet Child o’ Mine’ was just Slash practising a string- skipping exercise – in fascinating contrast to the super-produced sound on their Chinese Democracy album, which cost thirteen million dollars and took fourteen years to complete. Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’s ‘I Put a Spell on You’ was meant to be a love-song ballad, but he and the band got raging drunk in the studio and instead cut the insanely dark classic we know, which he can’t even remember recording despite it giving him his name. I hid three-week-old Holiday Sidewinder underneath my big jacket and snuck her into a Screamin’ Jay gig at the Harbourside Brasserie, determined to see him play again after witnessing him open for the Bad Seeds at Selina’s in the mid-80s. Some would consider that a mistake, but hell, I don’t regret it one bit. The show was so wild and great, and my tiny baby slept through it with nobody the wiser.

The weird chord at the beginning of The Police’s ‘Roxanne’ was created by Sting sitting down on the piano accidentally; you can just hear an echoey laugh follow it, setting a slightly discordant edge to the song.

Sinatra dropped the lyric sheet for ‘Strangers in the Night’ and improvised with the now classic ‘do bee do be doo’ outro. Fontella Bass also dropped her lyrics while she was recording ‘Rescue Me’ and so hummed her way out of the outro. Those funny little non-word sounds Freddie Mercury made throughout Queen and David Bowie’s gargantuan hit ‘Under Pressure’ were from a first take where he was trying to figure out what to do. While recording ‘(Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay’, Otis Redding broke into his joyful whistling solo without warning, as a placeholder for a third verse he planned to write and record; he died three days later, so we’ll never know what we missed, but the song is absolute perfection as it is.

Time, space and budget are other factors we’re indoctrinated to believe need to be a certain way in order to achieve excellence in recording and a competitive, professional edge. So many hits, so many albums explode that notion. The album Led Zeppelin took all of thirty-six hours to make, including setting up, playing and mixing, and was paid for out of Jimmy Page’s pocket. The Beatles’ Please Please Me album was recorded in one day, with ‘Twist and Shout’, the final song, recorded in a single take. The moody Miles Davis classic Kind of Blue was also put to tape in one day.

Butch Vig recorded Kurt Cobain’s guitar and vocal for ‘Something in the Way’ with one mic while Kurt lay on a couch. Bruce Springsteen’s masterpiece Nebraska was taped on a cheap 4-track recorder. The Doors’ L.A. Woman was recorded in their rehearsal room, with Jim Morrison doing his vocal takes in the bathroom doorway. The Streets’ acclaimed debut album emerged from a rented Brixton flat, Mike Skinner’s vocals recorded in a cupboard. The influential Bon Iver folk album For Emma, Forever Ago was recorded while he was alone in an isolated Wisconsin cabin. David Gray’s White Ladder was self- recorded in his apartment and self-released; after being picked up by a bigger label, it hit number one in the UK a year after it first came out, eventually becoming one of the biggest-selling albums of all time. Billie Eilish’s career-making, multi-Grammy-winning opus When We Fall Asleep, Where Do We Go? is a bedroom recording made with her brother Finneas in their family home. In response to the disbelief this was met with, Finneas tweeted, ‘People act like recording billie’s album in my bedroom was difficult but in reality, every time I’m in a fancy ass studio it takes them a fucking hour to get the aux cord working.’

A lot of people out there will try to teach you the rules of rock’n’roll, but the only rule worth listening to is that there are no rules.

Music can be your own personal Vegas, a great big fantastical gamble where anything goes.

Tom Waits’s ‘Big in Japan’ opens with the ear-grabbing sound of him wildly banging on a dresser in a Mexican hotel. He has recorded in cars, barns, chicken coops and his son’s bedroom, and has claimed that the weirdest place for him to record now is a studio.

Radiohead recorded OK Computer at Jane Seymour’s haunted Tudor mansion – she gave them the keys and told them to feed the cat. The Rolling Stones made Exile on Main St. in an old mansion in France, hooked up to the game-changing mobile recording truck they’d originally set up to record tracks for Sticky Fingers. Sigur Rós recorded their album ( ) inside an empty swimming pool in Iceland, in a made-up language they called ‘Hopelandic’. Pink Floyd’s A Momentary Lapse of Reason was recorded mainly on Dave Gilmour’s houseboat on the Thames. The Black Keys moved up from the basement where they’d recorded their first two albums to take over an abandoned tyre factory for their self-produced third album Rubber Factory. The Cowboy Junkies’ The Trinity Session was recorded in an Ontario church around one microphone. Prince Harvey managed to secretly record his debut PHATASS using computers in the Soho Apple store, with the assistance of a couple of friendly ‘team members’, going five hours a day, five days a week for four months, never sitting down, just using the GarageBand software and the built-in mic. Bank vaults, castles, space stations, water tanks, prisons, the Taj Mahal, and the inside of a West Berlin pillar are just some of the other less travelled spaces that have contributed to impressive recordings.

Do what it takes to make what you want. I’ve always found a way to make my records my way. Although the idea of signing a record deal has certain alluring qualities – such as somebody else’s cash and influence leading the way – I know what I like, and I feel like I believe in myself more than anyone else is ever going to. I also like to work to my own schedule; so many artists get stuck in a waiting game of being unable to release their work until it fits somebody else’s timeline. I like to create at my own speed without compromise, then move on to my next project, so I decided early that I’d be better off forming my own label for my albums.

The hardest part has always been getting the budget together upfront for the inescapable recording and pressing expenses. The slow way is to save up ’til you’ve got the funds; the fast way, which isn’t necessarily the smartest way considering most records take years to pay themselves off – well, mine do anyway – is to do it on credit and hope for the best. The only credit card I was ever able to qualify for was the Harvey Norman one – the only one available without any means test – which had a cruelly high interest rate and a two-thousand- dollar limit. This card was the only way I could bankroll my early albums, and I’d pay it back religiously until the coffers were full again and I could afford to fund the next record. Luckily, living frugally has always come quite naturally to me; my only real indulgences have been expensive underwear, delicious food and making albums.

Trust your intuition. Any time that I’ve had to be convinced to do something that my first instinct was to run from, I’ve generally found myself wondering why I didn’t stick to my guns. Conversely, sometimes you just know when things are right for you. Intuition is a mysterious and inexact wisdom but it is nearly always proved correct. Lee Hazlewood wrote ‘These Boots Are Made for Walkin’’ for himself or another male singer to perform, and was not at all convinced when Nancy Sinatra heard it and knew she had to record it. She told him it sounded too harsh and abusive coming from a man but was intriguingly subversive coming from a ‘little girl voice’. She earned two Grammy nominations for it to drive home the point that a woman’s intuition is always right.

Turn everything upside down. Andrés Segovia famously referred to the guitar as being ‘like an orchestra looked at by the reverse side of the binoculars’. Albert King played his guitar upside down. The hugely influential classical guitarist Django Reinhardt played with only three working fingers; he’d lost the use of the other two after a fire in the Romani caravan he called home. Joni Mitchell suffered childhood polio that left her unable to form chords correctly, leading her to experiment with more unusual ones that created her signature jazzy, otherworldly sound. You can turn limitations into assets, into your unique signifiers. When you feel stuck, when it feels impossible, find a new perspective to make a new kind of sense of things.

Please yourself. Taste is utterly subjective. Prince wrote ‘Kiss’ as a country song for the band Mazarati, who were not at all impressed and turned it down. Realising how good it was, he reclaimed it, and after recording it he took it to his label, who didn’t like it but begrudgingly agreed to release it anyway. Who knew best? All hail Prince!

When the head of Columbia first heard Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’ he called it ‘a disaster’ and refused to release Various Positions, the 1985 album it was on, stating, ‘Look, Leonard, we know you’re great. But we don’t know if you’re any good’. The album was eventually released by tiny independent label Passport Records; Leonard was fifty at the time.

Monet was told his paintings were formless, unfinished and ugly. After Elvis’s first performance at the Grand Ole Opry, he was advised to return to driving trucks in Memphis. Spielberg’s attempts to get into film school were rejected three times. Shakira was told her voice resembled the bleating of a goat. Walt Disney was fired for not being creative enough. J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series was rejected by twelve publishers. Oprah Winfrey was deemed ‘unfit for TV’ by a Baltimore station early in her career. You know what they say about opinions – it’s true. Float your own boat.

Laugh at everything and anything could happen. Beck’s teen anthem ‘Loser’, written as a joke, launched him on a course to rock stardom. ‘Stuck in the Middle with You’ was Stealers Wheel’s deadpan attempt at mocking Bob Dylan, but the joke was on them when they became known for that song more than any other. The Beastie Boys classic ‘Fight for Your Right (To Party)’ was written on a napkin in under five minutes as an ironic joke, a simple diss track about bratty frat boys intent on partying; it became their defining hit – and unfortunately also an anchor around their necks, as it dragged them into its self- destructive vortex while they partied hearty and stumbled drunkenly all the way to the bank. They stopped playing the song live in 1987 to escape its hedonistic grip. But they’re still getting those sweet royalty cheques for it.

Dream. Keith Richards wrote the world famous ‘Satisfaction’ guitar riff in a dream, sat up in bed and recorded it, then went back to sleep. When he heard it the next morning, he thought it sounded ‘folksy’ and didn’t like it – luckily Mick thought otherwise and insisted they work on it. Johnny Cash dreamed the iconic trumpet parts for ‘Ring of Fire’, at a time when the trumpet wasn’t welcome in country music. Cash also had a dream in which he met Queen Elizabeth; she was sitting on the floor with a friend, laughing, and when he walked in she gasped and said, ‘Johnny Cash, you’re like a thorn-tree in a whirlwind!’ He thought about that dream for seven years, trying to work out the meaning behind it, before finding that phrase in the Bible. He put it into a poem he’d been writing, ‘The Man Comes Around’, which became the title song of his comeback album with producer Rick Rubin.

Paul McCartney wrote the melody for ‘Yesterday’ in a dream; on waking he played it perfectly, which made him certain he’d heard it somewhere before. He spent months asking friends if they’d heard the tune, trying to work out where he’d plagiarised it from, before finally deciding it must be his own and writing real lyrics in place of the ‘Scrambled Eggs’ version he’d been messing with.

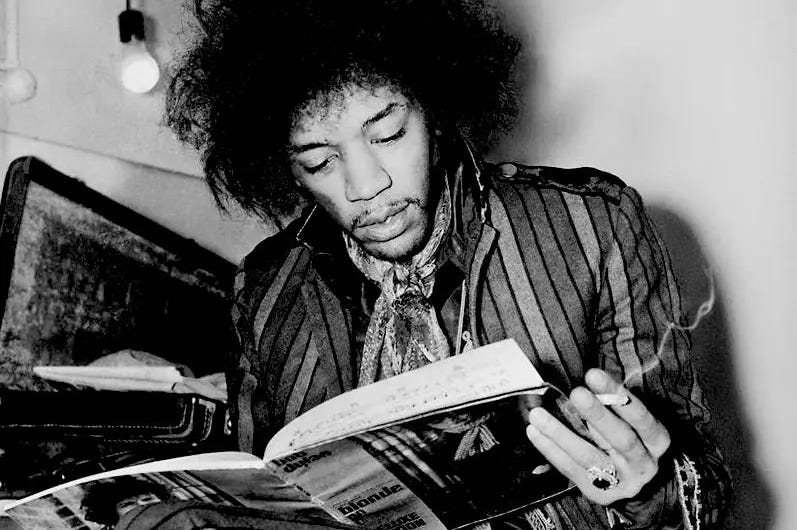

‘Purple Haze’ was lifted from a dream Jimi Hendrix had after falling asleep reading a sci-fi novel: he was walking underwater surrounded by a purple haze. Michael Stipe dreamed he was at a New York party with a bunch of people whose names had the initials L.B., such as Lester Bangs, Lenny Bruce and Leonard Bernstein; they were all eating cheesecake and jellybeans, and singing the lyrics to R.E.M.’s ‘It’s the End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)’. I especially like that such a weird dream created the amazing big singalong chorus. The ending of Handel’s ‘Messiah’, which he had been intensely struggling with, came to him in a dream. Beethoven claimed to have dreamed many of his piano sonatas; sometimes they were even played on fantastical instruments. Dreams unlock rigid thoughts and reconnect them in ways that can lead to creative breakthroughs, innovations and new discoveries.

The late John Prine, one of my very favourite songwriters, wrote a perfectly formed song with me in my dream one night. He was my Uber driver, in a cute little chauffeur cap, and we wrote the song as we drove to my destination, laughing all the way because we somehow understood each other’s funny brains. The song is called ‘The World Inside My Mind’. Since then I’ve felt warmly familiar and close with John Prine, as though it really happened. I’m tempted to give him songwriting credit:

There’s a place I always go

When the world’s about to blow

And all the walls are kinda caving in

I’ve got the secret handshake

The password and the mandate

I know that they will always let me in

Welcome to the world inside my mind

Sometimes I wish that I could live there

All the time

It’s at the end of every rainbow

When every lonesome whistle blows

Welcome to the world inside my mind

Strange dreams run in my family and, unlike many people, I always love hearing the details. I’m in awe of the extraordinary wildness of the human brain, its inexplicable abilities that we rarely tap into. In a dream, I bumped into Cec Condon everywhere I went, and he was always unreachable, deep in thought, lost in trying to solve mysterious algorithms for an upcoming recording. In real life I hadn’t seen him in a while, and when I finally saw him and told him about the dream, he couldn’t believe it; he’d been setting up his home studio with a 4-track, totally absorbed by figuring out how to record in there. Hard to know if that’s a coincidence or a psychic connection – I’m just glad we make music together. When I was living on the other side of the world and badly missed my friends and family, I’d often have wonderful dream visits that were almost as joyous and satisfying as the real thing.

Trust yourself. It’s entirely possible that we’re all far smarter than we think we are, and that dreams are our only evidence of this fact and the pathway to tapping into that cosmic intelligence. As a high school dropout, I cling to this theory and put a lot of faith in my self- education. I will never win at Trivial Pursuit, and I live in terror of those TV vox pop interviewers on the street who might ask me basic questions about geography, politics, maths or history and expose the stunning depths of my ignorance.

But I’ve gone deep when studying what I find important, and I can draw on what I need. Sometimes we just have to get out of our own way to find the answers we seek; sometimes we have to trust that we know and are capable of more than we realise.

Seventeen-year-old Hamburg girl Bianca Passarge dreamed she was dancing on top of empty wine bottles while dressed as a cat, then dedicated eight hours a day, for four months, to learning how to bring her dream to life. I’ve tried without luck to track down further information about this extraordinary attempt, but all I can find is one perfect photo that proves she accomplished it.

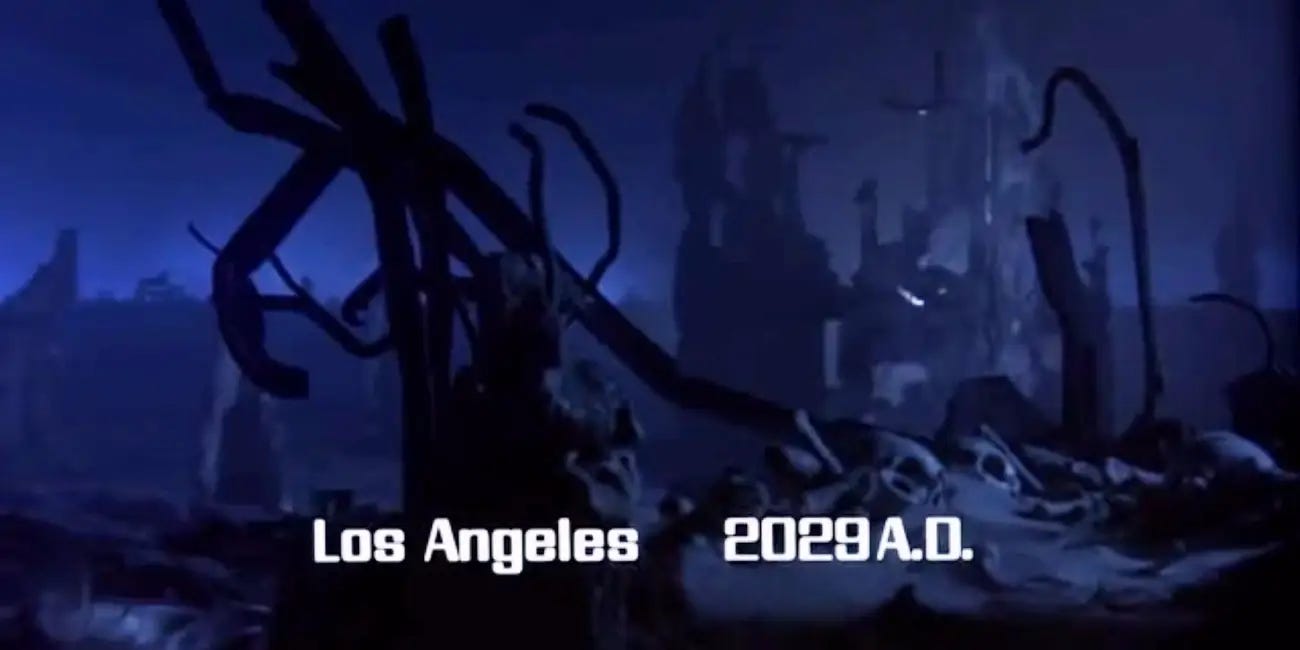

Edgar Allan Poe’s short stories were inspired by the ‘divine communication’ and ‘supernatural instruction’ he received in his dreams or nightmares. Mary Shelley conjured Frankenstein in a vivid ‘waking dream’ after Lord Byron challenged her to write a ghost story. Jack Kerouac believed dreaming ‘ties all mankind together’. Stephen King confided, ‘I’ve always used dreams the way you’d use mirrors to look at something you couldn’t see head on’ and has credited his dreams for producing the stories in Dreamcatcher, It and Misery. The director Christopher Nolan became obsessed with lucid dreaming and would practise waking himself up to harness his dreams, leading to the conception of Inception. Franz Kafka’s transformative tale Metamorphosis came out of ‘hypnagogic hallucinations’ he experienced as he was falling asleep, and The Terminator came to James Cameron in a fever dream.

When Thomas Edison recognised that many of his brilliant ideas came to him as he slumbered, he began to sleep while holding a rock and with a tin tray next to the bed, so that when he was in a deep sleep he’d drop the rock on the tray and the resulting clatter would wake him up, catching the dream. That some of the most definitive creations of our cultural world have emerged from dreamscapes is a lesson that remains fairly unexplored.

Nobody’s ever begged me for advice – I just have a tendency to accidentally write advice songs, like ‘Sometimes It’s Hard’, ‘Hold Your Lover Close’, ‘Mimic the Rain’, ‘The Things That Matter’, ‘Don’t Let Her Slip Away’, among others. But as much as I dish it out, I can also take it. You know what they say – you give the advice you need to hear yourself. I’ve learned most everything I know via the lessons I gleaned from songs like ‘Take It to the Limit’, ‘Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough’, ‘You Should Be Dancing’, ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right’, ‘Homegrown Tomatoes’, ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ and ‘Try a Little Tenderness’.

I once advised my daughter about an issue she was having; I told her, in a comfortingly vague Zen maternal fashion, ‘Just give yourself some space and listen to your heart.’ Her father firmly recommended, ‘This is no time to listen to your heart, you just need to act.’ Probably equally good advice in the long run and an excellent example of how utterly meaningless advice really is. Choose whatever resonates, whatever lights the way forward.

Some people like Bible quotes to live by, but my personal favourite piece of guidance might be this one, courtesy of the great outlaw country singer Waylon Jennings:

‘There’s always one more way to do things, and that’s your way, and you have a right to try it at least once.’

I hope you are doing things your own way, today and every day, and thanks for spending some of your precious time here with me reading Loose Connections!

If you enjoyed it, please let me know by leaving me a little heart or a comment or sharing it somewhere or with someone…

Rock on,

Lo x

(Today’s Loose Connections contains extracts from my book ‘Lovers Dreamers Fighters’, published by Harper Collins Australia in 2022)

Epic. Wonderful snapshots to engage with . One of your best. Double Bravo if I add your lovely tracks you dropped this week. Once again. Thank you.

That was top notch.

Well done and thank you.