“When I hear music, I fear no danger. I am invulnerable. I see no foe. I am related to the earliest times, and to the latest.” Henry David Thoreau

I played through a brawl once, at the Gladstone Hotel. The stage was on the same level as the dance floor, which was packed, the band (Slow Hand) was pumping and suddenly fists started flying in front of us until it was just a surreal melee of headlocks and grunting punches and my dad was to my right yelling ‘Just keep playing!’ and he looked like he knew what he was saying so we all looked at each other and silently agreed to keep going and the so band jammed on wild extended solos like we were providing the soundtrack for a fight scene in a cartoon or a bad action movie until eventually a bunch of cops turned up and broke it up and the dance floor cleared and as if nothing had happened we said ‘we’re gonna take a short break’ and all stepped outside to take some deep breaths and ask each other with beating hearts ‘what the hell just happened?’.

During the Civil War, in July 1863, a group of soldiers were ordered to burn down a fine mansion. A beautiful piano within caught their fancy and they decided to lug it with them to their nearby trenches in Jackson, where a Private Carter entertained the troops with rousing popular songs of the day until they realised they were under attack. There were terrible losses on both sides. After a short armistice to bury the mountains of dead because of the awful stench, Private Carter jumped back in the trenches and continued playing to comfort and distract the remaining soldiers. That bullet riddled piano is now on display in a museum in New Orleans, a moving, battle scarred monument to the ability of music to say the unspeakable.

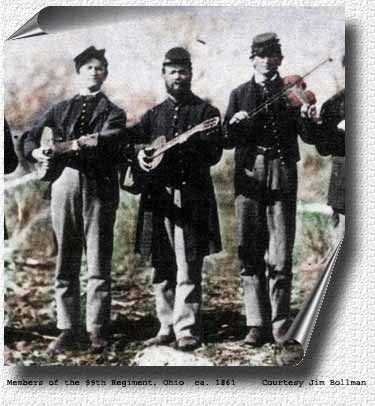

In this same war - as in all wars - music helped to keep up morale in the camps and to lighten the load of the challenging conditions. Patriotic anthems and love songs were played; the humorous ditty ‘Eatin’ Goober Peas’ was sung when soldiers had nothing left to eat but boiled peanuts. Publishers supplied troops on both sides with ‘songsters’, little books with lyrics of all the popular songs.

‘The Bonnie Blue Flag’ was a favourite marching song of the Confederate Army. When the Northerners occupied New Orleans, the publisher was jailed and a fine was issued for anyone caught even whistling the tune, including children, in an attempt to quell its subversive power.

Unofficial ‘Battles of the Bands’ sprang up between opposing encampments. Unioners played ‘Yankee Doodle Dandy’ and Confederates blasted ‘Dixie’ in return. As the troops grew tired, more nostalgic, sentimental tunes beloved by both sides, such as ‘Home Sweet Home’, would ring out, their voices united in song from the trenches, offering a brief soothing respite before they returned to killing each other the next morning.

Private Frank Mixson from the 1st South Carolina Volunteers described a situation where warring forces united over a song, cheering and jumping and down, throwing hats in the air: ‘Everyone went crazy’ He said the shared music brought a realisation of humanity to enemies and ‘had there not been a river between them, the two armies would have met face to face, shaken hands and ended the war on the spot.’

Artillery captain Thomas Key of Florence, Alabama expressed this strange unifying power of music: ‘The whole earth resounded and echoed with music this morning before the rising of the sun. Band after band commingled their soft and impressive notes, melting the hearts of some and buoying up the spirits of others.’

In the infamous WW1 Christmas Truce of 1914, when a British soldier noted there was only one more hour until it was Christmas and a German soldier responded by breaking out a baritone version of ‘Stille Nacht, heilige Nacht’. Both sides laid down their arms and joined in, working their way through the various Christmas songs in common to the many cultures represented, accompanied by harmonicas, bagpipes, and violins, exchanging cigarettes and trinkets, playing games and helping each other bury their dead. Sadly it was not possible for the ceasing of hostilities to endure.

Bands have accompanied units into major battles - boys as young as twelve in the drum and fife corps - providing rhythm and verve to motivate the soldiers’ efforts. Colonel Samuel W. Price of the 21st Kentucky Infantry described how music supported a protracted charge for his men: ‘The men advanced slowly, driving the enemy (cheering all the while, inspired by the soul-stirring music of the band) some twenty-five or thirty minutes.’

Music re-energised the exhausted troops on the road to Gettysburg: ‘At the end of forty minutes, all the bands struck up a lively tune. Our men sprang to their feet, and on we went. It was wonderful’ tells Colonel Robert McAllister.

General George Custer also believed in the power of music to inspire in battle: ‘We always have the band playing on the front in an advance, and tooting defiantly in the rear on retreat.’ Cavalry formations in The Battle of Waterloo were controlled by bugle calls with specific commands. The Scottish Division played bagpipes during the Battle of Normandy in 1944. In the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, British military drummers brought up the rear, and played throughout the battle, while over 200 soldiers were killed. During the Boer War, a twelve year old bugle boy was honoured for killing fleeing Boers. Thirteen year old Joseph Bara was killed while playing drums to keep spirits high during the French Revolution.

A Frederick Hitchcock gives this description of the Battle of Chancellorsville: One of the most heroic deeds I saw done to help stem the fleeing tide of men and restore courage was not the work of a battery, nor a charge of cavalry, but the charge of a band of music! The band of the Fourteenth Connecticut went right out into that open space between our new line and the rebels, with shot and shell crashing all about them, and played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the “Red, White, and Blue,” and “Yankee Doodle,” and repeated them for fully twenty minutes. They never played better. Did that require nerve? It was undoubtedly the first and only band concert ever given under such conditions. Never was American grit more finely illustrated. Its effect upon the men was magical. Imagine the strains of our grand national hymn, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” suddenly bursting upon your ears out of that horrible pandemonium of panic-born yells, mingled with the roaring of musketry and the crashing of artillery. To what may it be likened? The carol of birds in the midst of the blackest thunder-storm? No simile can be adequate. Its strains were clear and thrilling for a moment, then smothered by that fearful din, an instant later sounding bold and clear again, as if it would fearlessly emphasize the refrain, “Our flag is still there.” *

Music unites the beleaguered in a defiant shared humanity, a balm for weary souls, providing diversion from chaos and horror, reminders of home and family, emotional catharsis for grief, horror and fear at the very same time as it uplifts and stirs the fever required to unleash the carnage of war.

Crown Prince Wilhelm of Prussia took a famous opera singer to the trenches to uplift his soldiers. The enemy reportedly cheered and clapped until an encore was performed.

In one of the most notorious heroic acts of musical defiance in the face of certain death, the eight members of the two house bands onboard the ill-fated RMS Titanic played ‘Nearer My God To Thee’ as the boat sank to keep spirits afloat. A second class passenger reportedly said ‘Many brave things were done that night, but none were more brave than those done by men playing minute after minute as the ship settled quietly lower and lower in the sea. The music they played served alike as their own immortal requiem and their right to be recalled on the scrolls of undying fame’.

Shostakovich stated ‘Music illuminates a person and provides him with his last hope; even Stalin, a butcher, knew that, and that was why he hated music’. Six of Shostakovich’s ‘The War Symphonies’ - the Fourth through the Ninth - were composed in response to Stalin’s totalitarian regime; to subversively express his anti Stalin sentiment, his sadness and fury at the repression of both his own work and the people. Symphony No 4 was officially denounced as too dark and pessimistic during rehearsal and Shostakovich kept it under wraps until 1961 for his own safety. His ensuing compositions were lighter and were embraced wholeheartedly by the government - he was later forced to compose soundtracks for propaganda films for the survival of his family.

On August 9, 1942, Leningrad Radio Orchestra performed Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, written during the siege of Leningrad, for a ragged, hungry, war torn audience at the Philharmonic as a gesture of anti-German defiance. Instruments were placed in the empty seats of the many dead orchestra members. Oboe player Ksenia Matu reflected ‘[Shostakovich’s] music inspired us and brought us back to life; this day was our feast.’ Composer Dmitrii Tolstoi said Shostakovich’s Ninth Symphony ‘was giving Stalin the finger, but keeping his finger in his pocket.’ Though he faced accusations of cooperating with the regime, Shostakovich later called his war symphonies ‘tombstones for the victims of Stalin’.

Days ago in Odessa, opera singers who had been rehearsing for Verdi’s Aida and Il Trovatore instead sung the national anthem in front of the opera house as volunteers, many of them musicians and staff from the opera house, worked together filling sand bags to prepare for the predicted Russian bombardment. Instead of preparing for the productions they are learning how to use rifles and basic first aid. A Ukrainian brass band plays ‘Don’t Worry Be Happy’. Ballet dancers from the National Opera of Ukraine have joined military efforts, among them principal dancer Oleksii Potiomkin, who is chronicling his journey on Instagram. An unamed young Ukrainian violinist plays 19th-century Ukrainian folk song What a Moonlit Night in a bunker to lift the spirits of those sheltering. Citizens hiding underground across Ukraine are joining together in song to comfort each other. Scientific studies have shown that when a group of people sing together their heart beats synchronise.

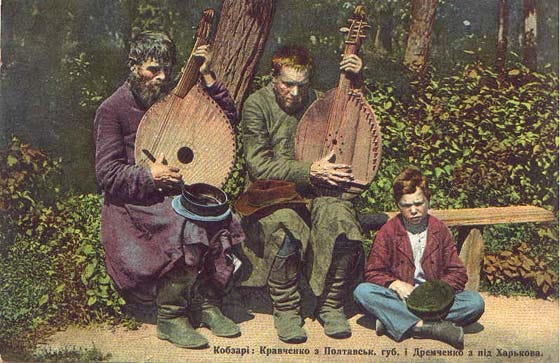

Two hundred classical musicians formed a flashmob in Trafalgar Square, London to play the Ukrainian National Anthem in a show of solidarity with Ukraine. Violinists from 29 countries, including nine currently in Ukraine, came together in only 48 hours to create a moving virtual performance of an old Ukrainian folk song titled Verbovaya Doschechka. In 1932, blind Ukrainian kobzars, musicians who travelled from town to town playing bandura and singing national folk songs, were lured to Kharkiv under the pretence of the first ever convention of kozbars, where they were lined up and executed by Soviet forces, in the belief that if they wiped out Ukrainian cultural connections to their past they would have a greater chance of controlling them. Like Harry Belafonte said, ‘You can cage the singer but not the song’. The songs have survived. Ukrainian ethnomusicologists, helped by The American Foklore Society are currently uploading musical archives for preservation from war zones.

“One good thing about music, when it hits you, you feel no pain.” Bob Marley

It may be naive and unlikely but what is life without hope - may the world find a way to unite together in song somehow someway soon.

Sources:

*p88. Frederick Lyman Hitchcock, War from the Inside: The Story of the 132nd Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion, 1862–1863 (New York: J. B. Lippincott, 1903), 218–19.

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.5406/americanmusic.28.2.0141.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A429a36b61df7da58dcf29d75364d1019

https://www.pitt.edu/pittwire/features-articles/ukraine-russia-history-through-music

https://www.classicfm.com/music-news/videos/ukrainians-singing-shelters-russian-raids/

https://www.newmarketnhhistoricalsociety.org/profiles/edward-richardson-musician-and-merchant/

https://ny77thballadeers.tripod.com/musicgath.html

I played plenty of Shostakovich when I was young. The 11th Symphony was incredibly powerful to be involved with. Its climax depicted the massacre in the 1905 revolution. Loving these articles, Lo.