Algorithms Are Not Your Friend

On Spotify, Independence, Mixtapes, Dreams & Disappointments

I still remember the first time I heard about Spotify.

It was 2009 and I had just spent thousands of dollars I didn’t have to travel to South by Southwest in Austin, Texas to be a ‘official showcasing artist’. I didn’t really know too much about it, but I knew it was a pretty big deal to get the offer and I’ve always believed in following opportunities and believing in myself, so I decided to go for gold.

As a showcasing artist, you are also allowed to attend the music business conference portion of the event for free, which runs all day every day. Considering the musical performances run pretty much all night every night, it can be a slog to drag one’s ass to listen to people pontificate on the dry business side of music by day, but I was determined to use this opportunity to access the insights from the best and brightest music minds. I loved being independent and self-managed but didn’t really know what I was doing or have many industry connections and I was excited to learn.

One of the seminars was on the future of music and someone – it may well have been Daniel Ek – told a room full of people about this incredible thing that could discern what music a listener preferred based on a complex array of data, and then recommend them similar artists. That instead of paying for individual artists/albums, people would pay a monthly subscription fee to listen to as much music by as many artists as they wanted. We were told this was going to be ‘the great equaliser’ for independent artists, because this would mean if your music had a similar vibe and feel to a hugely popular artist, your music would appear next to theirs in a natural flow on, and be presented to the listener in such a way they would discover you organically. The idea of being able to access this kind of exposure was exhilarating and felt egalitarian.

Like things were changing, and to be independent was becoming a smart and powerful choice, if you were willing to work hard, knew what was what and how to take advantage of these futuristic techy things.

Back in 2009, although indie artists could lug and mail their CDs to indie record stores for physical sales, they still needed to make a deal with an indie distributor if they wanted to get their music online – there was no way to get your own music on iTunes for example then.

Now we can easily and affordably access ‘aggregators’ ourselves and decide where we want to upload our music to be released online worldwide and sit alongside Mariah Carey or Imagine Dragons with no discernible difference between us and we can drill down on the minute details and data of the accounting and streaming numbers ourselves. It’s a wonderful thing, and it really is a ‘great equaliser’ (thank you Distrokid, I love you).

But let’s cut back to Spotify.

I still remember the thrill of seeing my music on there for the first time, of thinking that if my song just magically turned up as a ‘similar artist’ next to someone I hoped I sounded a bit like, that I would be growing my ‘fanbase’ (terminology that has always sounded creepy to me) and finding my people worldwide.

At that time in my life, I was a working musician, performing regular gigs in a thriving local music scene and doing haphazard little tours regularly, selling CDs at gigs, making a relatively tiny living compared to normal people, but almost enough to justify it to myself. I figured Spotify might be a small but reliable extra source of income.

I talked about it excitedly to other musicians, wide eyed for the future. I was thrilled when I became a ‘verified artist’, feeling like the last visible indicator of difference between ‘indie artist’ and ‘artist on a big label’ was erased.

We could all succeed solely on our merits, our music. I spent hours making carefully and lovingly themed playlists. We small indie artists were told this was a great thing to do for exposure but I’ve also just always been an obsessive playlist maker.

Before all of this, I had a bizarre contraption that was a CD to CD burner, and I spent literal days compiling mixtape CDs, one track at a time, and then burning individual copies for my friends. It was an act of love. Music was shared between friends by word of mouth and by mixtapes and by reading about something that hit you in a spot that made you run to a music store to listen.

People that gave you mixtapes/mix CDs found a special place in your heart and earned your eternal gratitude. I wrote quite extensively about this in my book so I won’t bang on too much about it here, but I still have every mixtape/CD I’ve been given and they still evoke strong feelings of gratitude and tenderness in me; Justine Clarke made me ‘Piccolo Bar Girl’ for driving music, Tex Perkins made me ‘Dirty Filthy’ which was a combination of the best Dirty Three and Stooges tracks with bonus Annette Peacock and Mick Geyer kept me constantly surprised with a fabulously random selection of music, much of which I’d never heard - the coolest thing about them was they broadened your mind and took you unexpected places and you often found a new artist to dedicate yourself to.

The problem with algorithmic playlists is that they funnel you deeper down into the same tunnel, with no unexpected twists and turns. For years my five CD stacker always had a Noah Taylor compilation in there because his dedication to making brilliant playlists of necessary music, obscure or otherwise, in every genre, was second to none. My car always had a selection of cassettes rolling around on the floor made by my friend Laurie Faen who turned me on to Lucinda Williams and John Prine and all kinds of folk and Americana and blues artists I probably would never have fallen for without him. I couldn’t afford to take risks on paying $30 for an album of music I hadn’t heard before, so the gift of a playlist was a gateway drug. If I became a fan, I was happy to pay $30 for the artist’s next album before even listening to it, even when I was earning $15 cash an hour. Two hours pay was a risk that was worth taking.

My eldest son is fourteen and has grown up with Spotify as our go to source for music. We left Australia when he was six, leaving all our physical music behind, so it’s all he’s ever known. It so natural to him to listen to any music he wants without thinking of paying for it, that he finds the concept of buying music utterly bizarre. He can’t understand why you ever would, and until recently, he defended Spotify’s business model as the way they had to do things to survive and seemed to feel it was idealistic sour grapes on the part of us music makers to complain about the pittance or less we were being paid in return for this ‘egalitarian’ system. ‘If they paid the musicians what they were asking for, the company would go broke’ was the argument that was bandied around.

Figures vary, but currently it takes around 250,000 streams for an artist that owns 100% of their own publishing and masters to make their first $1000. A single stream generates around 0.003 cents. Musicians were cast as unrealistic and greedy for complaining. My son, and I’m sure most younger people, felt the kind of loyalty and gratitude and love for Spotify that used to be given to cool music loving friends or taste-making music mags.

He loved the discovery features, how Spotify would suggest similar artists and he would feel a sense of excitement and pride as he’d watch a smaller artist begin to grow their numbers, much like I used to feel when I’d witness the Drones or the Dirty Three grow from playing to a tiny audience to massive loving crowds. He would introduce artists to me by telling me what their numbers were. ‘She’s got a million followers ’ was a way of saying someone was obviously really good and utterly deserving of such a following. I’m sure he thought I was just a curmudgeon who didn’t understand the world of modern music when I badly attempted to explain the deals between labels and Spotify that were going on behind the scenes to help an artist’s growth and that it wasn’t just word of mouth and that the algorithms were rigged and I just sounded like a jealous nobody.

Because Spotify’s focus on play numbers had created a world where artists and their songs were now judged on their play counts and followers. Where before you might discover an artist because you heard their music somewhere and liked it, and success could be measured on different levels such as audience engagement and critical reception, now artists like me, with low play counts, were immediately judged as unworthy and unsuccessful.

Some fans wear their records out rather than stream on Spotify. That can’t be counted. But you can’t hide the numbers and the indisputable fact is, low play counts make artists look bad. It affects opportunities for festival and gig bookings. Numbers create a culture of competition, which I don’t believe all music should be subjected to and the metrics of success shouldn’t be only numerically measured - although obviously the world of pop charts is its own thing.

But far from the promised dream of being placed in front of listeners due to similar styles moods, genres and atmospheres, the ‘similar artists’ I was lumped together with appeared to be based solely on our similarly low play counts. Or maybe I’m missing something. At one point the five ‘similar artists’ that were listed at the bottom of my artist profile included the atrociously named Babydick, some kind of death metal band, a girl-pop band called Futomomo Satisfaction, an obscure ambient techno duo, a ‘beats heavy’ artist called KB the Boo Bonic and a squeaky voiced teenager called Coco K with 1 follower who released a single single in 2013. I find it hard to believe we shared a ‘fanbase’.

I felt like I’d been relegated to the dregs of a forgotten basement bin. My visible Spotify playcounts downgraded all my other achievements, acclaim and measures of success as an independent artist and reduced me to an obvious failure. I gotta tell you it was somewhat depressing. And confusing. The ‘similar artists’ thing does, however, seemed to work reasonably effectively for more popular artists.

I never wanted to be one of those annoying artists constantly begging people to ‘follow me’ (but god, please, follow me!). But the way of the world is numbers and followers now and there’s no fighting progress and no amount of bitching about it will change it. The music business model has irrevocably changed. Adapt and survive. That’s OK, that’s what we’ve always done.

Daniel Ek caused a small furore in 2020 (mainly amongst musicians and industry people) when he told Music Ally that it was a ‘narrative fallacy’ that Spotify didn’t pay musicians enough per stream. He dismissed older artists who were frustrated with not being as successful as they once were, as not understanding the current musical landscape and stated ‘you can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough’, spruiking the idea of ‘continuous engagement’ with fans and summing up with ‘I feel, really, that the ones that aren’t doing well in streaming are predominantly people who want to release music the way it used to be released’.

Meaning the idea of putting your heart and soul into making the best album you could and then working your ass off to tour and promote it was now the mark of a deluded disgruntled dinosaur artist and what was now required was constantly dropping singles and new versions and remixes and collabs and stories and engaging with fans. I enjoy wondering how Lou Reed would have responded to that.

That the Spotify business model is artist unfriendly and exploitative on so many levels is no longer a shock and now just an accepted fact but most independent artists have still felt a sense of needing to be on Spotify, that despite its undeniably shitty ethics, it still has value as a potential discovery tool and you’re better off being on there than not. The carrot of being randomly added to a Spotify curated playlist, which has the power to suddenly boost streams dramatically (up to 360 million streams as reported here) is real and ever dangling.

The recent revelation by a former Spotify employee that these incredibly powerful, sometimes career changing playlists are each compiled by a single Spotify employee, who may not even be engaged with the genre they have been assigned, was shocking to a community that believed in the idea of music loving curators with secret identities, and often paid shonky companies who preyed on the desperation of clueless artists substantial sums to get you on ‘the radar’ of these ‘curators’. I know I considered it last time I released an album back in 2017, thinking maybe it was legit and a worthwhile investment. Artists truly swim in a sea of sharks, with promotion the bait. There are countless scams targeting independent artists posing as opportunities to break through/past/into a system that is still as tightly controlled by deals and relationships between labels, services, brands and other big businesses as it ever was.

The promised dream of an equal playing field that Spotify originally seemed to offer, has turned into a dystopian nightmare minefield, incomprehensible and seemingly unescapable. Spotify is now rolling out a paid promotional service called Marquee for new releases, available only to artists with 15k streams in the previous 28 days. Pay for play. Same as it ever was.

That Spotify has now been singled out as the ‘bad guy’ by choosing to keep the divisive, low hanging fruit of Joe Rogan over stand-up guy and beloved artist Neil Young makes the other streaming services look positively virtuous by comparison but as Liz Pelly pointed out in this excellent 2017 article for The Baffler ‘despite its conventional market viability, there are key differences between Spotify and its rivals, Apple Music and Amazon Music, which both have the luxury of capitalising on overpriced, fun-sized plastic and metal surveillance machines. For Apple Music, the bottom line is selling iPhones, laptops, iPads, and other hardware. Streaming music makes those products more valuable. For Amazon Music, the motive is similar; they aim to sell Alexa devices and Amazon Prime subscriptions.’ (*Update 8 Jan 2024: Liz Pelly’s new book Mood Music, investigating and exposing Spotify’s shifty regime is out today!)

Bandcamp, the most preferred artist friendly digital music provider has emerged as the hero of independent artists attempting to survive a pandemic that has destroyed their income earning potential based on the hard physical work of performing and touring, and left bare the ugly carcass of the fact that they are now almost completely dependent on these streaming services who obviously don’t value their artistry and certainly don’t feel they have to pay for it.

There is a vocal contingent of people that proudly proclaim how they love to buy records and support artists directly (and goddamn do we love them), but the reality is most people just want to listen to music when they feel like it and feel like it’s not their problem to sort out the inequities of the world. Fair enough. There are far worse hardships to rail against than unfair pay for music creators. Besides all artists are rich right?

Having grown up the daughter of a musician, I have always known about the inequities and evils of the music industry and never expected to encounter anything different – after all, one of my dad’s songs has the telling lyrics ‘ripped off again, story of my life, ripped off again, how can I tell my wife?’. I have also read a towering stack of music biographies detailing the myriad ways in which guileless artists suffer at the hands of corrupt music industry deals. Of course, there’s some great stories out there too about artistic empowerment and brilliant management and teamwork and all those cool things but they tend to be a little rarer.

It’s little wonder I chose to be independent. I never believed anyone owed me anything, and believed no-one would ever work harder for me than I’d work for myself. I’ve tried very hard to keep up to date with technological advances and to be my own best advocate, and kept hold of my copyrights and the hope that continuously releasing quality work into the world is the best way to build a career.

Recently, Spotify released a statement that declared ‘A decade ago, we created Spotify to enable the work of creators around the world to be heard and enjoyed by listeners around the world’ and when I read that, I still feel that pang of altruistic possibility, that it is an exciting tool for connecting audiences and artists and they mean well and have our best interests at heart, but I know after the recent Joe Rogan/Neil Young drama they they value money over artistic integrity and social responsibility and so that concept is just built on a false sense of loyalty because it’s what’s they’ve sold us and I’ve bought into from the beginning, and because Spotify houses all my beloved playlists and because it’s the standard way of sharing playlists on every media platform and really what would we do without it?

But it’s way beyond time to face the fact that it’s a dream that’s soured, a system that’s corrupted and that Spotify’s face value veneer of supporting artists and songwriters by surprising them with showy billboards and playlists celebrating their achievements is little more than a cynical attempt to appear artist friendly while forcing them to acknowledge and promote Spotify in gratitude - in reality a slap in the face and the equivalent of an unhealthy, gaslighting relationship.

Maybe the idea that songs have actual value, that we depend on them for all kinds of reasons, for our broken hearted tears and our slow dances and our parties and funerals and uplifting shopping experiences, and that the people that create them and work hard on them might deserve renumeration for their efforts and that it costs money to produce them and promote them and package them and get them into the world and that maybe, just maybe, the idea that you can own all the music in the world for a small monthly subscription fee is just not sustainable and needs to be reconsidered and a workable solution found.

They sent a rocket to space, surely there’s some brilliant minds out there that can solve this puzzle. We all seem to agree everyone should be paid fairly for their work, but it feels like music makers are expected to accept we should be happy to be paid in little more than exposure - and we all know you can die from exposure.

I know this might be boring and too much information for those not actively engaged in the ups and downs of music creators rights (and believe me I could go on) but I just wanted to share a human story of a thrilling music service love affair that turned toxic and how I still struggle to break with it, as a listener, an artist and an engaged citizen who cares about the other people in my community and other workers in song.

Further notes:

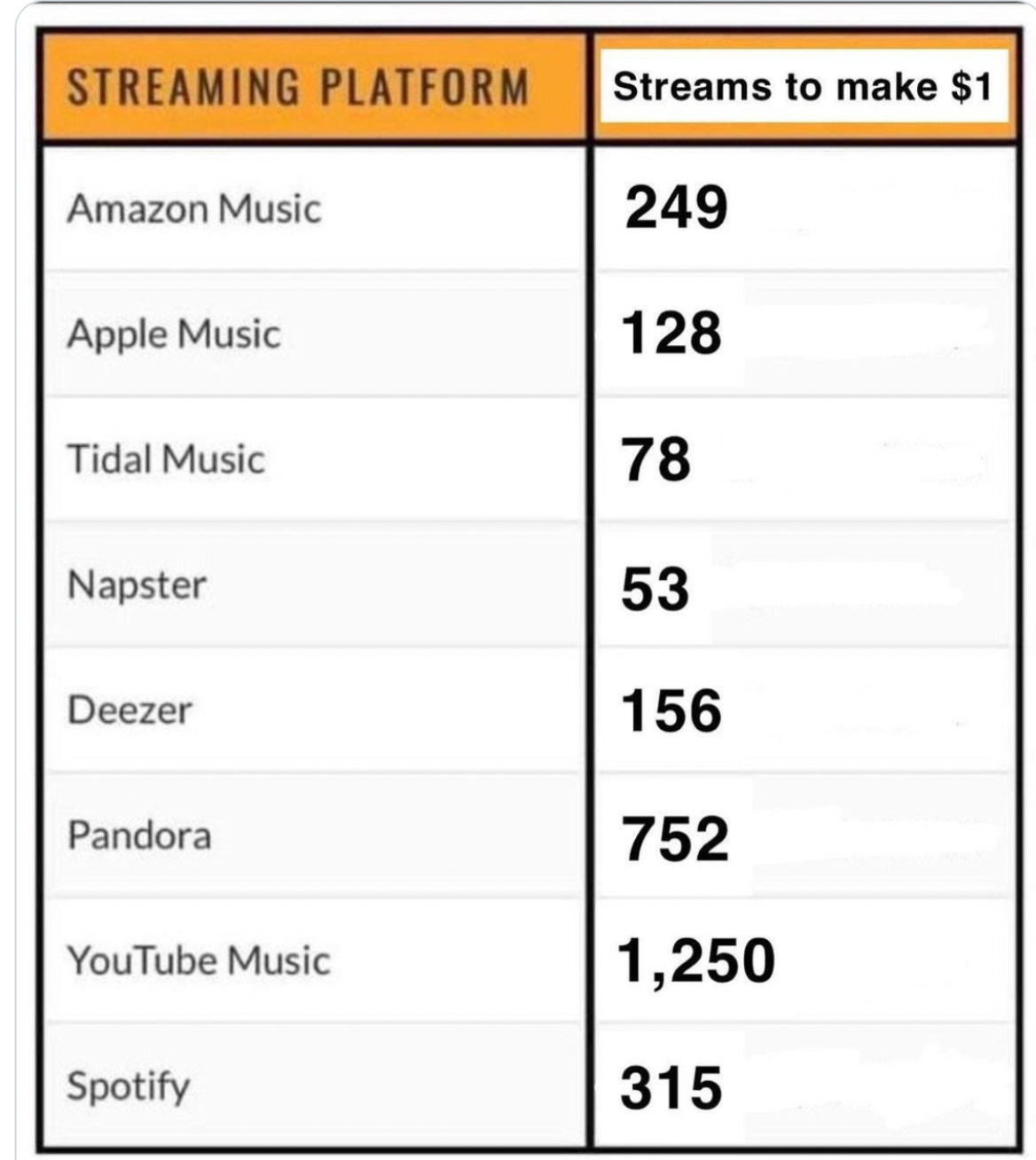

Here are a couple of infographics recently posted by the artist TPain. None of these figures are actually definitive, as there are many things that come into play such as different streaming rates in different countries and different label deals. Anyway, they’re reasonably indicative of what rates artists are dealing with.

If you’re considering leaving Spotify, as an artist or paid subscriber, or just want to open up your options, but your beloved playlists are stopping you, you can easily copy any playlists to another service of your choice with the clever Songshift app. I’m currently in the process of doing this - actually my son is doing it for me.

Musician Tom Gray from Gomez has led a campaign called #brokenrecord, bringing awareness and fighting for fairer compensation from Spotify and other streaming services. It’s gathering steam and forcing reflection on an unwilling industry, including a UK Parliamentary inquiry into streaming economics. He says ‘The existing system financially disincentivises a broader scope of music and music taste. It is leading us towards a cultural vanishing point and, for individual artists faced with the haywire economics of a revenue pool divided by total streams, towards a financial vanishing point too.’ He goes on to say ‘No one denies that there are some out there who are making close to a decent living from streaming. I know a few and I applaud them, but I don’t believe I’ve met a band yet whose income is largely derived from streaming. I haven’t met a solo artist who isn’t on less than a 50/50 split with their label who has close to that decent living.’

There’s a fascinating blog post here relaying the attempts of an independent artist trying to find/buy followers, exposure, playlists.

This is a real reader comment from an article exposing the shoddy streaming rates across the board: ‘If you can’t figure out how to compose and distribute and promote music that enough people want to hear so that you can get paid, well, maybe you should do something else. Give up.’ I’ve seen similar ones a million times.

Fun fact; Spotify Wrapped, the end of year wrap up of your most listened to artists and songs that is proudly shared across all social media platforms and excitedly greeted by listeners across the world, was the unacknowledged creation of an unpaid intern.

i'm old fashioned in that i haven't gone down the track of 'streaming' my music - i still buy it for the exact reasons you have laid out here....also, the idea of a computer/machine suggesting music really irks me - much better to have it come from a heart and a brain.

Really great read. As an independent artist in a similar boat, it’s very relevant. Thanks! 🎺🎺